Franz Kafka

Biography

Authored By: Ben Streeter

Edited By: Anna Mukamal, Helen Southworth

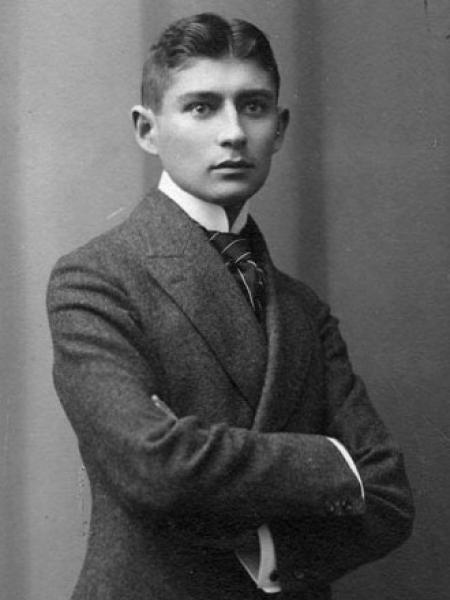

Books, Franz Kafka said, “must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us” (Letters 16). Kafka was born in Prague in 1883. The oldest son of Hermann and Julie Kafka, he had three sisters, Valli, Elli, and Ottla, and two brothers who died in infancy. His father was a wealthy Jewish Czech businessman who did not support Franz’s literary aspirations. Kafka’s conflict with his father would become the main theme of his writing (Rabate 64), in which he was able to express things that he could not say directly to his father (Letter to His Father 69). Kafka was intolerably burdened by his father’s unfavorable judgments, and it was clear to his best friend, Max Brod, that Kafka remained “unable to free himself from his father despite his critical attitude toward him” (22-3).

He started publishing in his mid-twenties in literary periodicals: the bimonthly Hyperion (1908-1909), the Prague-German newspaper Bohemia (1909-1911), and the Herder-Blätter (1912), a short-lived journal sponsored by the B’nai B’rith society to promote Jewish culture and co-edited by Willy Haas, a school friend of Kafka and Max Brod. Another friend of Haas, with whom he later co-founded a weekly paper in 1925, was Ernst Rowohlt, who started the Rowohlt publishing company in Leipzig in 1908, published Kafka’s first book, Meditation, in 1912. The company was renamed the Kurt Wolff publishing company in November 1912. Wolff was a German publisher who later established Pantheon Books in 1942. His archive is held by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

In 1913, an annus mirabilis for modernism in which Proust published Swann’s Way, Kafka published “The Judgment” in Arkadia, an anthology edited by Brod and published by the Munich-based Kurt Wolff and a second book, The Stoker, with the same publisher, won a significant literary award, the Theodor Fontane Prize, named after Fontane, a major German novelist, journalist, and critic of the 19th century. In “The Judgment,” a father sentences his son (Kafka) to death (Diaries 215).

During World War I, an important German expressionist monthly published in Leipzig, Die weissen Blatter, published Kafka’s The Metamorphosis in October 1915. The publication was co-founded in 1913 by Kurt Wolff and Erik Ernst-Schwabach, who was the founder of the journal’s parent company, Verlag der Weissen Bücher (Stach Decisive 405). “Verlag” is German for publishing company. Kurt Wolff also published The Metamorphosis in book form in November 1915, followed by The Judgment as a book in 1916. That year, Robert Musil visited Kafka in Prague.

Although Kafka published his first books less than a decade after his first writing in periodicals, he continued to publish in monthlies and weeklies throughout his career. The literary journal Marsyas published Kafka’s stories “An Old Manuscript” and “A Fratricide” in 1917. The magazine was founded by the playwright Theodor Tagger.

Kafka was diagnosed with tuberculosis in September 1917. In October and November, Der Jude published “Jackals and Arabs” and “A Report to an Academy.” The German monthly was started in 1916 by co-founders who later played a big role in Kafka’s publication history. One of them was German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, who met Kafka in 1913 and later offered him an editorial position. Kafka declined (Medin 22). The other was Salman Schocken, a longtime advocate of Kafka’s who founded the Schocken publishing company in Berlin in 1931.

Schocken published many of Kafka’s works, including his diaries and Before the Law in 1934, as well as other German-Jewish writers such as Walter Benjamin and the Buber-Rosenzweig translation of the Bible (Poppel 20-49). The publishing house was confiscated by the Nazis in late 1938. It was reopened as Schocken Books in New York in 1946, with Hannah Arendt as a senior editor and plans for new editions of Kafka.

In 1919, Kafka published two books with Kurt Wolff, In the Penal Colony and A Country Doctor. He also wrote the unpublished Letter to His Father. Kafka’s first works to appear in a language other than German were Czech translations published in the Prague literary weekly Kmen (“the stem”) on the advice of Milena Jesenská, Kafka’s lover and translator; Kmen published “The Stoker” in 1920 (Stach Insight 330). In 1921, the weekly German newspaper Karpathenpost published Kafka’s “From Matlarhaza.” The paper was founded in 1880 and published in Kežmarok in what was then Austria-Hungary.

“A Hunger Artist” first appeared as a story in 1922, in a quarterly German literary magazine founded in 1890, Die Neue Rundschau. Kafka left The Castle unfinished in 1922. In April 1924, Prager Presse, a German newspaper published by the Czech government, published “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk.”

Kafka died on 3rd June, 1924, in Kierling and was buried on 11th June in the Jewish cemetery in Prague-Strasnice. A memorial service was held on 19th June at the Little Theater in Prague. Kafka had enjoyed the theater, and though his fictional aims were serious, at his readings, he and his audience were prone to laughter (Harman 301).

After his death in 1924, A Hunger Artist was published as a book by Verlag Die Schmiede, an avant-garde literature publishing house in the 1920s in Berlin that also published works by Alfred Döblin, Joseph Roth, and Rudolf Leonhard. Kafka was translated into English for the first time in transition, an influential modernist journal cofounded in Paris in 1927 by Maria and Eugene Jolas and distributed at Shakespeare and Company. It was the first journal to publish excerpts by James Joyce of what would become Finnegans Wake. Eugene Jolas translated Kafka’s “The Judgment” for transition in 1928.

After Brod handled the publication of The Trial (1925) with Verlag Die Schmiede, as well as The Castle (1926) and Amerika (1927) with Kurt Wolff, Kafka’s books were translated into English and published throughout the 1930s. Kafka’s translators, Willa and Edwin Muir, convinced Martin Secker to publish The Castle in 1930 (Mellowm 310-12).

Secker started the Secker publishing company in 1910. It became Secker & Warburg in 1936, when it was purchased by Frederic Warburg. Known for being both anti-Fascist and Anti-Soviet, Secker & Warburg's publications included the works not only of Kafka but also of Norman Douglas, George Orwell, C. L. R. James, Colette, and Thomas Mann. The archives of Secker & Warburg are split between the University of Reading, the University of Illinois, and the Lilly Library in Indiana. The Hogarth Press published both Edwin Muir and his wife Willa Muir. Edwin Muir also championed Kafka as a critic. Secker trusted the Muirs after they had translated a bestseller, so the Muirs then translated The Trial (1937) and Amerika (1938) for Secker. The Muir translations were long held as the authoritative version of Kafka in English, but scholars have since scrutinized their translations (for more on the Muir translations, see Harman).

In the United States, Philip Rahv was an early champion, publishing essays about Kafka in The Southern Review and The Kenyon Review in 1939. In 1937, Rahv founded the Partisan Review. For the inaugural issue of his new periodical, Rahv edited and published the first essay about Kafka to appear in an American little magazine (Ackerman 109). In the following years, Rahv and the Partisan Review published three Kafka short stories (1939-1942), a section from Kafka’s diaries (1946), and essays about Kafka by Max Brod (1938) and Hannah Arendt (1944).

Schocken Books in New York reissued the Muir translations in 1946 and commissioned translations of Kafka’s diaries and letters in the 1950s. With growing international recognition, scrutiny over Max Brod’s translations and edits grew. As early as 1940, Salmon Schocken said in a memo that new translations would be required. But Brod refused to allow access to the Kafka manuscripts in his Tel Aviv apartment (Samuelson).

New editions of Kafka’s posthumous works became possible in 1956, when Brod allowed access to Kafka’s papers (Samuelson). The threat of war prompted Brod to move most of the archives, including The Castle, to a Swiss vault. While Kafka had instructed Brod to destroy his papers, Brod’s ambition was to edit his friend’s texts into classics of so-called world literature. As the renowned Kafka scholar and translator Mark Harman has noted, Brod was always “discovering” new Kafka material, announcing in the late 1960s that he had found a new Kafka story. When asked where Brod found the new Kafka piece, he simply said: “Why, here in my desk, of course!” (11-2).

In 1961, Kafka’s heirs granted permission to Oxford’s Malcolm Pasley to deposit Kafka’s archives in the Oxford Bodleian Library. The manuscript of The Trial remained with Brod until 1968, when he left it to his heiress. She sold it in the late 1980s. A German library purchased it in 1988 at Sotheby’s for $2 million. A 2016 court ordered that Kafka’s remaining papers be transferred from Brod’s heirs to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem.

A new edition of The Castle, translated by Mark Harman and based on the restored text, was published by Schocken Books in 1998. Harman’s translation of The Castle won the Modern Language Association’s inaugural Lois Roth Award for outstanding translation in 1998. Two more new translations based on the restored text were issued by Schocken in 2008: Amerika, also translated by Mark Harman, and The Trial, translated by Breon Mitchell.

Recent scholarship on Kafka has looked at the narrative techniques used to produce estrangement in Kafka, comparing them with those of Maurice Blanchot. Another focus of recent scholarship on Kafka has been the law, specifically applying the work of Jacques Derrida to understand the boundaries of law as a discipline, as it relates to the adjacent disciplines of literature and philosophy.

Works Cited

Ackermann, Paul. “A History of Critical Writing on Kafka”. The German Quarterly, 23.2, 1950.

Adler, Jeremy. "Stepping into Kafka's Head". Times Literary Supplement, October 13, 1995.

Brod, Max. “Kafka: Father and Son”. Partisan Review, 1938.

Harman, Mark “‘Digging the Pit of Babel’: Retranslating Franz Kafka’s Castle”. New Literary History, 27.2, 1996.

Kafka, Franz. Diaries, 1910-1923. Translated by Joseph Kresh and Martin Greenberg, Schocken Books, 2000

---. Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors, Penguin Random House, 2016.

---. Letter to His Father. Translated by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins, Random House, 2015

Medin, Daniel. Three Sons: Franz Kafka and the Fiction of J. M. Coetzee, Philip Roth, and W. G. Sebald, Northwestern UP, 2010.

Mellown, Elgin. “The Development of a Criticism: Edwin Muir and Franz Kafka”. Comparative Literature, 16.4, 1964.

Bibliography

Selected Bibliography

Caputo-Mayr, Marie Luise and Julius M. Herz. Franz Kafka: An International Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Literature. G. Saur, 2000.

Duttlinger, Carolin. The Cambridge Introduction to Franz Kafka. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Richard T. Gray, R. V. G., Rolf J. Goebel, and Clayton Koelb. A Franz Kafka Encyclopedia, Greenwood Press, 2005.

Stach, Reiner. Kafka: The Years of Insight, Princeton University Press, 2013.

Stach, Reiner. Kafka: The Decisive Years, Princeton University Press, 2013.

Stach, Reiner. Kafka: The Early Years, Princeton University Press, 2017.

Franz Kafka — Archival Material

The Bodleian Library in Oxford, UK

The German Literature Archive in Marbach am Neckar, Germany

The National Library of Israel in Jerusalem

Full Bibliography

Amerika: the missing person: A new translation, based on the restored text, trans. Mark Harman, Schocken Books, 2008.

The Blue Octavo Notebooks, ed. Max Brod, trans. Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins, Exact Change, 1991.

The Castle, trans. Anthea Bell, Oxford University Press, 2009.

The Castle: A new translation, based on the restored text, trans. Mark Harman, Schocken Books, 1998.

The Complete Stories, ed. Nahum N. Glatzer, Schocken, 1976.

Franz Kafka Diaries 1910-1923, trans. Joseph Kresh and Martin Greenberg, Schocken Books, 2000.

A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, trans. Joyce Crick, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Letters to Felice, ed. Erich Heller and Jurgen Born, rans. James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth, Minerva, 1992.

Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors, Penguin Random House, 2016.

Letter to His Father, trans. Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins, Random House, 2015.

Letters to Milena, ed. Willy Haas, trans. Tania and James Stern, Minerva, 1992.

The Man Who Disappeared (Amerika), trans. Ritchie Robertson, Oxford University Press, 2012.

The Metamorphosis and Other Stories, trans. Joyce Crick, Oxford University Press, 2009.

The Office Writings, ed. Stanley Corngold, Jack Greenberg and Benno Wagner, trans. Eric Patton with Ruth Hein, Princeton University Press, 2008.

The Trial, trans. Mike Mitchell, Oxford University Press, 2009.

The Trial: A new translation based on the restored text, trans. Breon Mitchell, Schocken Books, 1998.