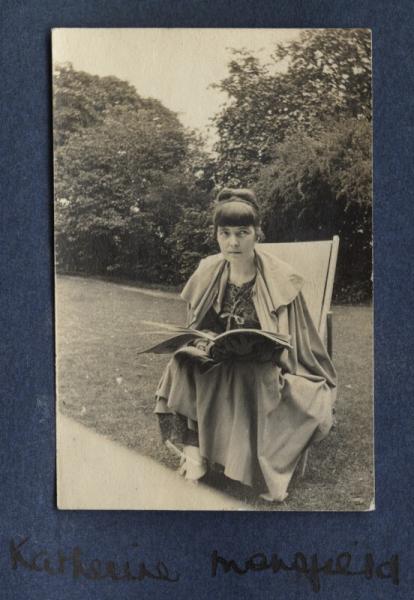

Katherine Mansfield

Biography

Authored By: Gerri Kimber

Edited By: Claire Battershill

Katherine Mansfield (originally Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp) was born into a well-to-do family in Wellington, New Zealand on 14 October 1888, the third of five children. Following an education in England from age fifteen to eighteen at Queen’s College in London, she found New Zealand society stifling and dull. In 1908, aged 19, she finally persuaded her parents to let her return to England to become a writer. Within a few months of arriving in England, she became pregnant and when the father refused to marry her, she married a virtual stranger instead. Having second thoughts, she left him on her wedding night. Her exasperated mother, Annie Beauchamp, travelled from New Zealand, arriving in London in May 1909, not knowing her daughter was pregnant. She took Mansfield to Bavaria, fearing she might be ‘suffering’ from possible lesbian tendencies, for which, at that time, a water cure – a German speciality – was deemed particularly helpful. Her mother was back on the return boat to New Zealand within a fortnight, and immediately upon her arrival she cut her wayward daughter out of her will. In June 1909, alone in Germany, Mansfield suffered all the horrors of a still birth. She did not return to England until January 1910, however, but in the meantime had several affairs, one of which resulted in her contracting gonorrhea. The disease was not formally diagnosed until 1920, by which time it had become a severely debilitating illness masked by the symptoms of her tuberculosis, also contracted at this time. Mansfield was living the ‘free life’ and that meant ‘free love’. Lacking the pills and antibiotics which protected the new free women of the 1960s and 1970s, she suffered damaging consequences – unintended pregnancies and venereal disease, which in turn lowered her resistance to tuberculosis.

During two more difficult years in England, Mansfield underwent at least one abortion, probably two, changed her name from Kathleen Beauchamp to Katherine Mansfield (she hated the name Kathleen and Mansfield was her middle name), and eventually set up home with the critic John Middleton Murry in 1912. In 1911, she had published her first book of short stories, In a German Pension, based upon her experiences and recollections of her stay in Bavaria. Her life from 1912 then settled to a more domestic, though still nomadic, existence. Mansfield and Murry were finally able to marry in 1918, following her divorce. From this point on, because of her tuberculosis, she was hardly ever in England, spending many months near the Mediterranean, and then Switzerland, on the advice of doctors. Bliss and Other Stories was published in 1920, followed in 1922 by The Garden Party and Other Stories. In October 1922, three months before her death, she entered George Gurdjieff’s esoteric community at Fontainebleau, just outside Paris, drawn by the spiritual philosophy of its founder. She died there on 9 January 1923, aged just 34. Mansfield was a charismatic, highly intelligent woman who lived life to the full, who experimented with all sorts of ways of living, and who paid bitterly for her mistakes later in her life. But throughout, her main raison d’être was always her writing – nothing else was truly important.

Mansfield’s fiction – and literary modernism as a whole – is associated with a rejection of conventional plot structure and dramatic action in favour of the presentation of character through narrative voice. For Dominic Head, “the plotted story . . . is set against the less well structured, often psychological story; the ‘slice-of-life’ Chekhovian tradition. It is to this tradition that the stories of the Modernists (those of Joyce, Woolf and Mansfield in particular) are usually said to belong” (16). Mansfield was present at the beginning of the modernist movement as one of its most exciting and cutting-edge proponents, and modernist tendencies can be found throughout her short stories. Mansfield employed free indirect discourse, literary impressionism, and the innovative use of time and symbolism, through which she offers glimpses into the lives of individuals and families captured at a certain moment, frozen in time like a painting or snapshot.

Mansfield’s earliest schoolgirl publications were printed in antipodean magazines, but soon after her arrival in London, she started publishing short stories in journals and little magazines such as the New Age, Rhythm, the Blue Review and the Signature. Her first published book, In a German Pension (1911), collected together many of her New Age stories into a place-based story cycle, demonstrating her natural proclivity for the genre. Set in a German spa town, an unnamed female narrator describes the daily routines of the guests in a typical German ‘pension’ or boarding house, as they undertake their various ‘cures’. These stories rely on hegemonic, imperial undertones, and the unnamed, first person colonial narrator (for she speaks English, but is not English), offers a subversive element to the cycle.

As Anna Snaith notes, “As [Mansfield] negotiated her place in avant-garde, literary London, she did so via a consideration of how she might ‘write’ New Zealand […] in the context of key modernist magazines” (111). Resonances of such an approach would continue on in her fiction, for many of her later stories are set in New Zealand. However, their subject matter no longer concerned the brutal or raw aspect of colonialism, but rather the minutiae of daily life, thus putting Mansfield at the forefront of modernist writing, and relegating any postcolonial characteristics to a mere detail.

Nevertheless, this early postcolonial stance of course enhanced Mansfield’s modernist outlook, where the notion of being ‘an outsider’, as Janet Wilson reveals, enables the ability to challenge the hierarchical status quo “of the metropolitan centre over the underdeveloped periphery, of male modernists like Joyce, Eliot, and Yeats, over women writers, of modernist genres of novel and poetry over that of the short story” (1). Mansfield herself remained an ‘outsider’; as Elizabeth Bowen affirms, “In London, she lived, as strangers are wont to do, in a largely self-fabricated world. […] Amid the etherealities of Bloomsbury, she was more than half hostile, a dark-eyed tramp” (128). Indeed, Mansfield would occasionally dress as a Maori, perhaps, as Bridget Orr notes, in order to exploit the exoticism of her background, but also, perhaps, as means of enhancing her ‘otherness’ within a metropolitan context.

Having met Murry in December 1911, Mansfield soon became involved in the editing of Rhythm, and by the time the little magazine folded in March 1913, she had risen to the position of joint editor, alongside Murry. Her personal contributions to Rhythm over the course of the magazine’s short life consisted of eleven poems, seven stories, six book reviews and two editorials, the latter co-written with Murry. This was in addition to her duties as an assistant-editor and then joint-editor, when her influence on the magazine’s contents and contributions was marked; many items which did not bear her authorial name would nevertheless have been edited or revised by her. She used a variety of names for her contributions to Rhythm: Katherine Mansfield, Boris Petrovsky, Lili Heron, and The Tiger, almost certainly to disguise the fact that her contributions were so numerous, and in the case of Boris Petrovsky, affirming the little magazine’s wider European remit.

Indeed, Mansfield, together with the other foreign contributors who gathered round this little magazine, engendered an exotic ‘foreign’ air, expanding out of England and looking towards a creative horizon that encompassed not just Europe – East and West – but the whole world. Mansfield herself, as assistant and then co-editor and through her own connections, fostered the magazine’s remit to escape beyond the confines of London – for both its contributions and its sales. At the height of its popularity, in Issue 7 of August 1912, Rhythm was naming seven distributors in France, two each in Poland and Germany, and single distributors in America, Finland and Russia. As a young, thoroughly ‘modern’, colonial New Zealander living in London, with a passion for the ‘new’ and the ‘modern’ in music, literature and art, Mansfield could not have wished for a more creative home.

The Blue Review, the successor to Rhythm, ran for only three months from May to July 1913, edited by Murry, with Mansfield as an associate-editor (though with far less influence), her role seemingly limited to correspondence (McDonnell 56). In 1915, Murry and D. H. Lawrence set up another little magazine, the Signature, publishing just two issues in October. Mansfield contributed a story to each issue, using the pseudonym Matilda Berry.

During the spring of 1915, whilst on a visit to Paris, Mansfield began writing a long story, initially called “The Aloe”, which gradually, over the course of the next two years, would be polished and condensed into “Prelude”, longer than anything she had previously written, and necessitating a different publication avenue to that of the magazine / journal. Mansfield’s novella was taken by the Woolfs and became the Hogarth Press’s second publication. Printing of the book began in earnest on 9 October 1917; Mansfield wrote to Dorothy Brett just two days later: “I threw my little darling to the wolves and they ate it and served me up so much praise in such a golden bowl that I couldn’t help feeling gratified. I did not think that they would like it and I am still astounded that they do” (O’Sullivan and Scott 330-1). It was officially published on 11 July 1918, in a run of 300 copies. As Jenny McDonnell notes, “in ‘Prelude’, Mansfield consolidated her theoretical approach to the short story form as an erasure of the authorial perspective from the narrative” (78). Initially c.26,000 words, her increasingly modernist editorial stance reduced the length to c.17000.

Here is the same passage in both texts:

(“The Aloe”) Dawn came sharp and chill. The sleeping people turned over and hunched the blankets higher – They sighed and stirred, but the brooding house all hung about with shadows held the quiet in its lap a little longer.

(“Prelude”) Dawn came sharp and chill with red clouds on a faint green sky and drops of water on every leaf and blade.

Almost three lines in the first instance are condensed to just over one line in the second. In “Prelude” a scene is presented, and the reader must visualize the image, subjectively, for him- or herself.

On 26 August 1918, Mansfield and Murry moved into ‘The Elephant’, the nickname for their tall, grey house at 2 Portland Villas, East Heath Road, Hampstead (which today is the site of the only Blue Plaque to Mansfield in England). Murry and his younger brother Richard set up their own private press in the basement (in an unsuccessful attempt to emulate the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press), called the Heron Press, which, however, never really got off the ground. The first publication was Murry’s Poems, 1917-1918, and the second – and final – publication, appearing on 15 February 1920, was Mansfield’s story Je ne parle pas français, printed in a small, limited edition.

Mansfield’s second book-length volume – Bliss and Other Stories – was published by Constable on 2 December 1920, containing 14 stories (including “Prelude”), written over the previous five years, several of which had been published in a variety of magazines and journals. Overtly modernist in tone and form, the volume confirmed Mansfield as an innovator of the modernist short story. However, the collection was advertised in the Athenaeum (then edited by Mansfield’s husband, John Middleton Murry) as “the ‘something new’ in short stories that men will read and talk about, and women will learn by heart but not repeat” (Anon., 3 Dec 1920, p. 778), provoking Mansfield’s anger at being promoted in this seemingly lowbrow way. Indeed, the episode culminated in her removing Murry as her agent, and appointing a professional agent, J. B. Pinker, instead.

Now in a more commanding position as a popular professional writer, Mansfield’s agent was able to demand higher prices for the serialisation of her stories in large circulation papers such as the Sphere and the London Mercury. Her final, prolific writing period of 1921-22, would see her publish 17 stories in six different papers, and culminated in the publication of The Garden Party and Other Stories, again by Constable, on 23 February 1922. It was the last collection published in her lifetime, containing 15 of her finest stories. She died from tuberculosis in January 1923, at the age of just 34.

Murry would go on to publish a number of Mansfield volumes after her death, including fiction, poetry, letters, a ‘scrapbook’ and ‘journals’, the latter two compiled from a disparate quantity of loose sheets, notebooks and diaries – the detritus of a writer’s life – none of which was ever intended for publication. This publishing strategy certainly harmed Murry’s own reputation: his subsequent literary ostracization was mainly a result of the overexposure of his dead wife’s work and his aim to publish as much of her literary remains as the public could stomach.

Indeed, Sylvia Lynd spoke for most of literary London in the 1920s when she decried Murry’s actions, claiming he was ‘boiling Katherine’s bones to make soup’ (qtd in Tomalin 241), whilst Frank Lea, Murry’s biographer, explained how by the 1930s, an opinion poll taken at Cambridge revealed him to be ‘the most despised literary figure of the time’ (52). But was Murry, after all, right to publish his wife’s papers? Would Mansfield, the writer of three volumes of short stories, have become such a literary icon without Murry’s actions? His various editions of her letters and notebooks, for example, were considered minor classics for much of the twentieth century, translated into many languages, and gained Mansfield thousands of admirers around the world. The only fly in the ointment was Murry’s editing, which deliberately sanitized Mansfield’s personal writing, contributing to the sense of a false persona, and which was only revealed following his death in 1957, with the eventual sale of Mansfield’s original manuscripts and the subsequent publication of unexpurgated editions of her letters and notebooks.

The accessibility and popularity of Mansfield’s stories prompted Wyndham Lewis at one point to dismiss her as nothing more than “the famous New Zealand Mag.- story writer” (qtd in Alpers 372), but though accessible to a general audience, this did not mean that she compromised on her modernist technique. By the end of her life, as McDonnell affirms, “she had finally succeeded in negotiating a space for her work that challenged the distinction between the ‘literary’ and the ‘popular’, ultimately occupying both spheres at once” (141-2). Her contribution to modern literature as an innovator of the modernist short story is now widely recognized, and many of her stories are considered modernist masterpieces.

Works Cited

Alpers, Antony. The Life of Katherine Mansfield. London: Jonathan Cape, 1980.

Bowen, Elizabeth. ‘A Living Writer.’ Cornhill Magazine 1010 (Winter 1956-7): 120-30.

Head, Dominic. The Modernist Short Story. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Lea, F. A. The Life of John Middleton Murry. London: Methuen, 1959.

McDonnell, Jenny. Katherine Mansfield and the Modernist Marketplace: At the Mercy of the Public. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Orr, Bridget. ‘Reading with the Taint of the Pioneer: Katherine Mansfield and Settler Criticism.’ Critical Essays on Katherine Mansfield Ed. Rhoda B. Nathan. New York: G. K. Hall, 1993. 48-60.

O’Sullivan, Vincent, and Margaret Scott, eds. The Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield. 5 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1984–2008.

Snaith, Anna. Colonial Woman Writers in London 1890-1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Tomalin, Claire. Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life. London: Viking, 1987.

Wilson, Janet. ‘Introduction: Katherine Mansfield and the (Post)colonial.’ Katherine Mansfield and the (Post)colonial. Eds Janet Wilson, Gerri Kimber and Delia da Sousa Correa. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013. 1-11.

Bibliography

Katherine Mansfield Principal Works (in order of publication)

In a German Pension. London: Stephen Swift, 1911.

Prelude. Richmond: Hogarth Press, 1918.

Je ne parle pas français. Hampstead: Heron Press, 1919.

Bliss and Other Stories. London: Constable, 1920.

The Garden Party and Other Stories. London: Constable, 1922.

Katherine Mansfield Posthumous Publications (selection, in order of publication)

The Doves’ Nest and Other Stories. London: Constable, 1923.

Poems. London: Constable, 1923.

Something Childish and Other Stories. London: Constable, 1924.

Journal. Ed. John Middleton Murry. London: Constable, 1927.

The Letters. 2 vols. Ed. John Middleton Murry. London: Constable, 1928.

The Aloe. London: Constable, 1929.

Novels and Novelists. Ed. John Middleton Murry. London: Constable, 1930.

The Scrapbook. Ed. John Middleton Murry. London: Constable, 1939.

Collected Stories. London: Constable, 1945.

Letters to John Middleton Murry, 1913–1922. Ed. John Middleton Murry. London: Constable, 1951.

Journal, Definitive Edition. Ed. John Middleton Murry. London: Constable, 1954.

The Collected Letters. 5 vols. Eds Vincent O’Sullivan and Margaret Scott. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984-2008.

The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks. 2 vols. Ed. Margaret Scott. Canterbury: Lincoln University Press, 1997.

The Edinburgh Edition of the Collected Works of Katherine Mansfield. Vols 1 and 2 – The Collected Fiction. Eds Gerri Kimber and Vincent O’Sullivan. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012.

The Edinburgh Edition of the Collected Works of Katherine Mansfield. Vol. 3 – The Poetry and Critical Writings. Eds Gerri Kimber and Angela Smith. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

The Urewera Notebook by Katherine Mansfield. Ed. Anna Plumridge. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015.

The Edinburgh Edition of the Collected Works of Katherine Mansfield. Vol. 4 – The Diaries of Katherine Mansfield, including Miscellaneous Works. Eds Gerri Kimber and Claire Davison. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

The Collected Poems of Katherine Mansfield. Eds Gerri Kimber and Claire Davison. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

Katherine Mansfield Society. http://www.katherinemansfieldsociety.org