Omega Workshops, Ltd

Description

Authored By: Hana Leaper

Edited By: Claire Battershill

,Edited By: Nicola Wilson

The Omega Workshops was a British design cooperative opened to the public at 33 Fitzroy Square in July 1913. Artist and critic Roger Fry (1866–1934) was the principle founder and director, and artists Vanessa Bell (1879–1961) and Duncan Grant (1885–1978) served as co-directors. The cooperative was motivated by the requirement to provide regular paid work for young post-Impressionist artists, and the ambition to redesign modern life to accommodate their hopes for modern people. Later, it became an important bastion of the peace movement, providing employment for conscientious objectors, as well as a gathering space for talks and exhibitions.

The nucleus of the Omega team was formed from artists from the Grafton Group, an exhibiting society formed by Fry in 1913. The Grafton Group had in turn had been born of artists disillusioned by the unenterprising direction that Bell’s Friday Club, founded 1905 had begun to take. These ambitious and talented young artists included the Omega directors Henri Doucet, Henri Gaudier Brzeska, Wyndham Lewis, Winifred Gill, Nina Hamnett, Dora Carrington, Cuthbert Hamilton, Frederick Etchells, Jessie Etchells and Edward Wadsworth. They formed a clan whose styles and politics became increasingly disparate in a very short time and amongst whom enmity soon sprang up.[1] Despite the unfortunate fallings-out, the founding principle was for the artists to work here in a cooperative spirit, sharing ideas and ideals. In the fundraising letter Fry foregrounded this communal effort calling ‘co-operation… a first necessity’ and claiming that many of the artists involved ‘have already formed the habit of working together with mutual assistance instead of each insisting on the singularity of his personal gifts.’[2]

In addition to this anonymous artisan approach, the Omega had other aesthetic agendas including a desire to ‘create forms expressive of the needs of modern life with a new sympathy and directness’.[3] ‘Free play’, ‘delight’ and ‘expressive quality’ were the terms Fry used to convey this ambition to decorate homes, cafés and workplaces to suit their twentieth century occupants.[4] Fry explicitly acknowledged the precedent of the Arts and Crafts movement, yet called The Omega ‘Less ambitious than William Morris, they do not hope to solve the social problems of production at the same time as the artistic.’[5]

Until the 2009 exhibition ‘Beyond Bloomsbury: Designs of the Omega Workshop 1913-19’, the Omega has been regarded as something of a failure by many commentators, both contemporaneous and recent. Fry himself ruefully called it ‘ill-fated’.[6] However, this project was an important moment in the careers of many of the artists involved, when they produced a high volume of aesthetically experimental and socially engaged work.

The Omega artists were aware of German Expressionist techniques and were interested in woodcut production. This resulted in several woodcut publications under the Omega imprint. Whilst other presses were struggling to remain open during the war, Fry was drawn to publishing due to his belief that continuing to produce and disseminate art and literature could ‘limit the cultural damage of the war.’[7] Grace Brockington argues that the four works published ‘made a statement of Fry’s pacifist priorities through the high quality of their design and production.[8]

Neither Fry nor his co-directors had much experience of publishing or of printmaking. With typical vigour, Fry ‘immersed himself in the technical processes of printing’, seeking guidance from JH Mason, a distinguished member of the printing and book design faculty at the Central School of Arts and Crafts between 1905-1940.[9] Realising that the means of production were beyond the Omega’s capacity, he contracted a professional printer called Richard Madley to produce the books. Madley’s premises were at 151 Whitfield Street, just around the corner form Fitzroy Square. The Hogarth Press also turned to Richard Madley for the second edition of Kew Gardens in 1919.

The first Omega publication Simpson’s Choice: An Essay on the Future Life (1915) by Arthur Clutton-Brock, contained three full-page woodcuts by Roald Kristian. An edition of 500 copies (plus review copies) was printed in a volume measuring 11 1/4 x 9 inches, bound in cloth-backed decorative boards.

Men of Europe (dated 1915, issued 1916) came next. This was Fry’s translation of Pierre Jean Jouve’s Vous êtes hommes. The eight leaves measure 9-1/4 x 11-1/2 inches, and the seven woodcuts by Roald Kristian were printed in maroon by Richard Madley under the direction of the Omega Workshops. Grace Brockington argues that Kristian’s illustrations augment the ‘explicitly pacifist message’ of the text.[10]

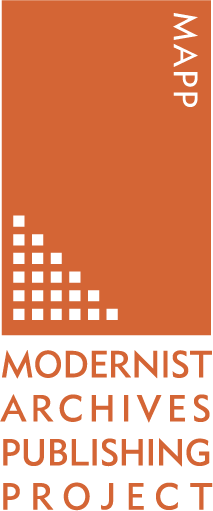

The third work, published 1917, was Lucretius on Death: being a translation of Book III, lines 830 to 1094 of the De Rerum Natura. This was a translation of Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius Carus’ exhortation against the fear of death by Robert Calverley Trevelyan. This book was illustrated with a cover designed by Roger Fry and executed by Dora Carrington – the bottom of the design incorporates the Omega logo.

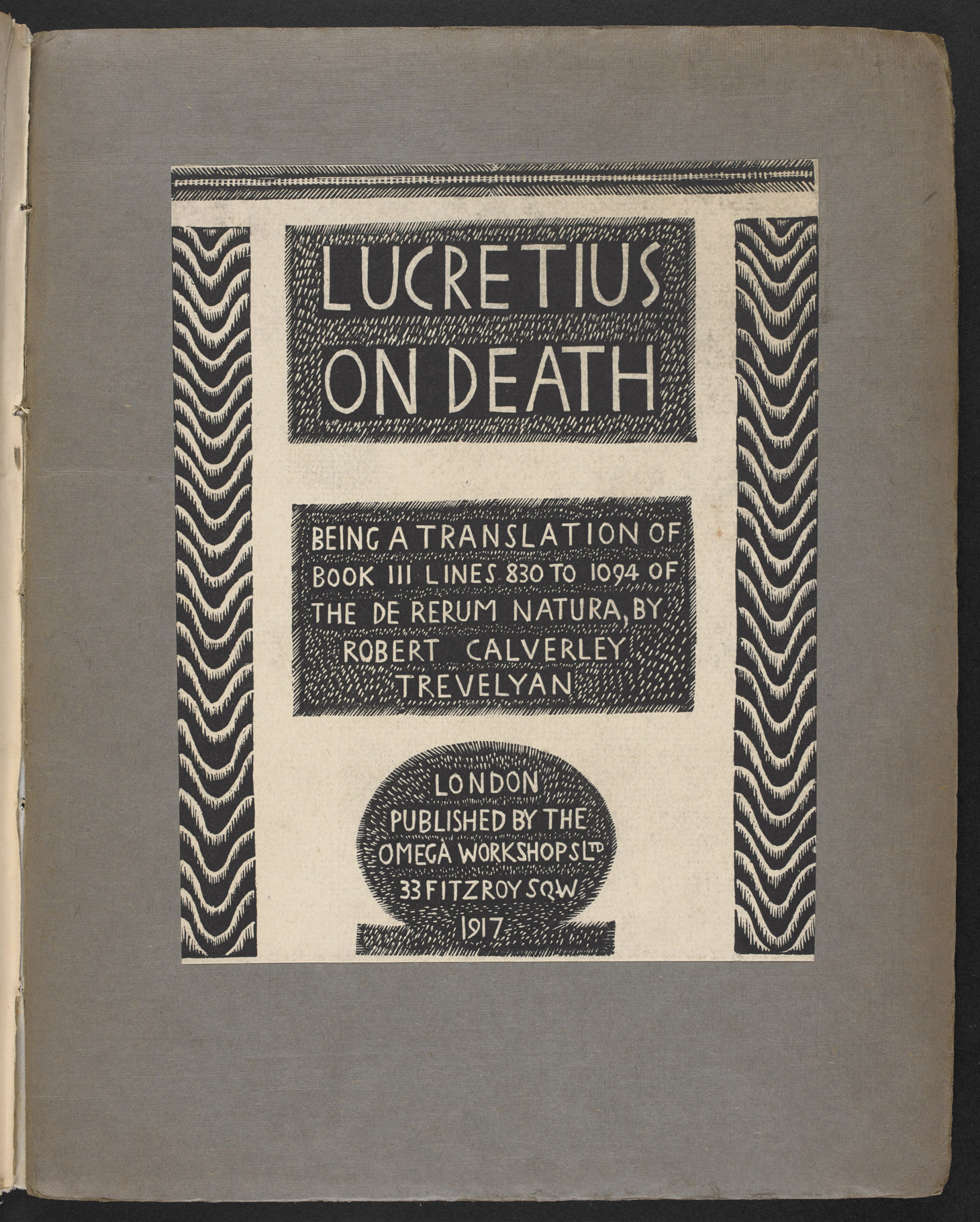

Isabelle Anscombe records that Original Woodcuts by Various Artists: ‘had originally been intended for publication by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s new Hogarth Press, but Vanessa disagreed with Leonard about who should retain artistic control and the production was taken over by the Omega.’[11] Printed in an edition of 75 copies, Original Woodcuts contains fourteen prints on various subjects by seven different artists, with hand-printed pink paper covers.

Frances Carey and Antony Griffiths show the contents of the volume in order as follows:

Roger Fry (1866-1934): 'Still Life', 180 x 108mm

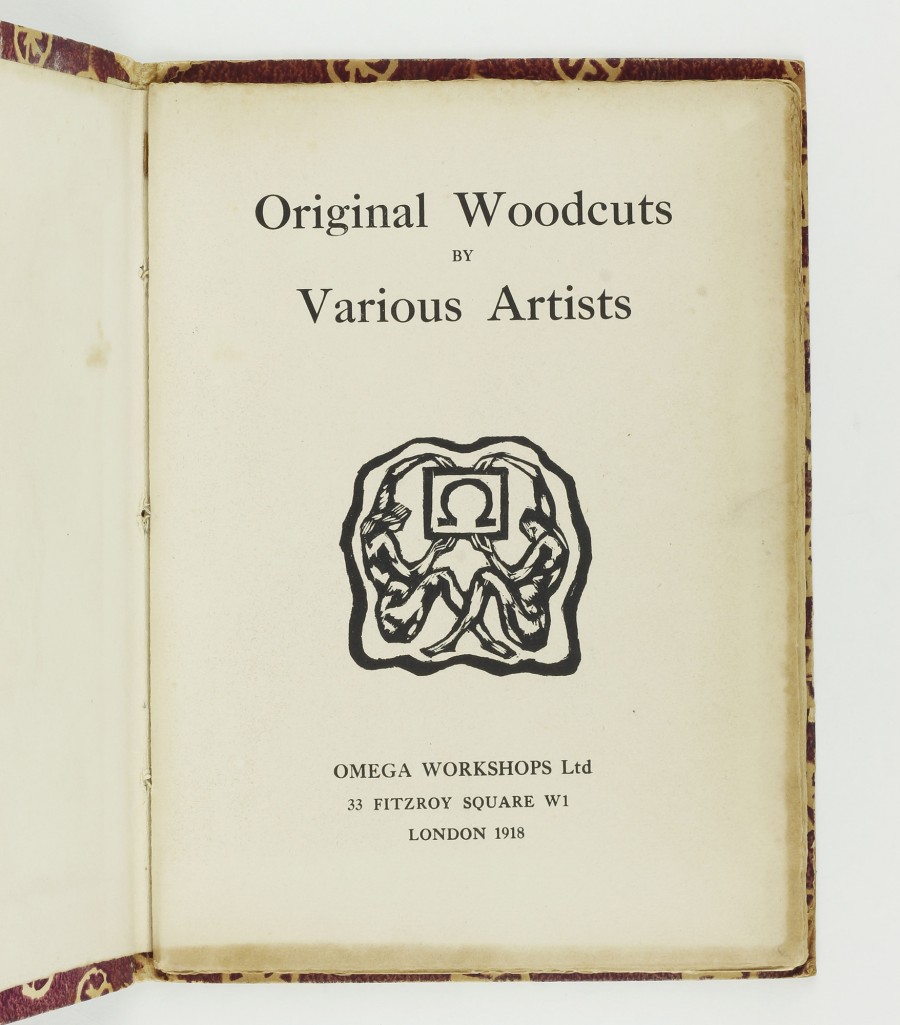

Mark Gertler (drawing, cut by Roger Fry): 'Harlequinade', 137 x 140mm

Vanessa Bell (1879-1961): 'Dahlias', 154 x 109mm

Duncan Grant (1885-1978): 'The Hat Shop', 185 x 109mm

Roger Fry: 'The Cup', 154 x 109mm

Simon Bussy (1870-1954): 'Black Cat', 242 x 127mm

Roger Fry: 'The Stocking', 184 x 109 mm

Roald Kristian (b.1893; date of death unknown):'Animals', 71 x 113 and 95 x 147mm

Vanessa Bell: 'Nude', 185 x 109mm

Edward Wolfe (1897-1982): 'Ballet', 110 x 185mm

Duncan Grant: 'The Tub', 110 x 185mm

Edward McKnight Kauffer: 'Study', 127 x 112 mm

Edward Wolfe: 'Group', 103 x 76mm[12]

By June of 1919, Fry, deeply in debt, closed the Omega. He had planned two further books that were never realised. They were Lucretius on Origins –a second extract from Lucretius, and a translation of Chinese poetry by Arthur Waley. The Bloomsbury artists’ interest in book design and print making continued at a moderate level, with Bell and Carrington producing woodcut illustrations for Hogarth Press books. In 1921 Hogarth hand printed and published 150 copies of 12 Original Woodcuts by Roger Fry. According to James Beechey ‘they sold out within two days, and in the new year two further impressions were issued to meet the unexpected demand. It was one of the most successful ventures the Hogarth Press had yet undertaken.’[13]

Archives and Papers

The Charleston Papers, SxMx56. Brighton: The Keep. http://www.thekeep.info/collections/getrecord/GB181_SxMs56

Correspondence and other papers relating to Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, Duncan Grant and others, 1896–1960, TGA 8010. London: Tate Gallery Archive.

[1] See Bell, Clive & Chaplin, Stephen. “The Ideal Home Rumpus.” Apollo 27, vol.80, 1964. 284-91.

[2] Fry, Roger. 'Omega Workshops Fundraising Letter.' A Roger Fry Reader, ed. Christopher Reed. London: University of Chicago Press, 1996, 196-197 (196).

[3] Fry, Roger. 'Prospectus for the Omega Workshops.' A Roger Fry Reader, 199.

[4] Fry, Roger. 'Preface to the Omega Workshops Catalog.' A Roger Fry Reader, 201.

[5] Fry, Roger. 'Prospectus for the Omega Workshops.' A Roger Fry Reader, 199.

[6] Fry, Roger. 'The Present Situation,' unpublished lecture, King’s College Library 1/111.

[7] Brockington, Grace. 'The omega and the end of Civilisation: Pacifism, Publishing and Performance in the First World War.' Beyond Bloomsbury: Designs of the Omega Workshop. Ed. Alexandra Gerstein. London: Fontanka, 2009: 60-69 (62).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Beechey, James. 'Introduction.' The Bloomsbury Artists: Prints and Book Design, ed. Tony Bradshaw. London: Scolar Press, 1999, 13.

[10] Brockington, Grace. 'The omega and the end of Civilisation: Pacifism, Publishing and Performance in the First World War.' Beyond Bloomsbury, 60-69 (62).

[11]Anscombe, Isabelle. Omega and After, Bloomsbury and the Decorative Arts. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984, 64.

[12] Carey, Frances & Griffiths, Antony. 'Avant-Garde British Printmaking 1914-1960.' London: British Museum Publications, 1990, 48.

[13] Beechey, James. "Introduction," The Bloomsbury Artists: Prints and Book Design, p.14.