Ahmed Ali

Biography

Authored By: Sheelalipi Sahana

Edited By: N/A

Ahmed Ali was born on 1 July 1910 in Delhi, India. He was born to Syed Shujauddin, a civil servant, and Ahmad Kaniz Asghar Beg. Ali completed his primary schooling moving around different cities before enrolling at Aligarh Muslim University in 1926, where he first took a class in English poetry. With help from his mentor and friend Eric C. Dickinson, a minor Oxford poet and teacher at the university, he published his first English poem in Aligarh Magazine. Not wanting to continue his studies in science to pursue a medical career, he transferred to Canning College, Lucknow University in 1927 and completed his degree in English Honours. It was during this time that he published the first of his short stories, titled “When the Funeral was Crossing the Bridge” in the Lucknow University Journal (1929). Proving to his family and friends that he had made the right choice by switching subjects, he graduated in first place, securing the “highest marks in English in the history of the university.” (Coppola 113)

1931 was a pivotal year for Ali, personally and professionally. He went on to complete his M.A. from the same university and took on the role of Lecturer in English at his alma mater. By this point, his Urdu language short story Mahavaton ki Ek Raat (“A Night of Winter Rains”) was published in Humayun and he produced a short English play Land of Twilight which would inspire his magnum opus Twilight in Delhi (1940). It was also during this year that he befriended Sajjad Zaheer in Lucknow and Mahmud Muzaffar in Mussoorie, both new writers. Along with Rashid Jahan, who was a medical doctor and a mutual acquaintance, the quartet published an Urdu anthology in 1932 that caused a storm in literary and religious circles.

Angare (Burning Embers) contained nine short stories and a short play; Ali contributed two stories, one a reprint of his earlier published “A Night of Winter Rains” and a newly-penned piece titled Baadal Nahin Aate (“Clouds Don’t Come”). The public reception to Angare was polarising; on the one hand, it was lauded by critics as radical and experimental and on the other, labelled obscene and sacrilegious by devout Muslims. The volume’s fame was short-lived as “the next three months saw a torrent of abuse and fatwas against the book and its authors, prompting the British Government of the United Provinces to ban it on 15 March 1933” (Jalil 149). In an interview he gave decades later, Ali called Angare “brave but adolescent” (Ali and JSAL 141).

Angare’s publication is regarded as a historically significant moment in South Asian literature. Along with the publication inaugurating a new age of modern Urdu literature, the quartet founded the All India Progressive Writers Association. As one of the founding members of AIPWA, Ali helped organise the group’s first meeting in 1936, which was held in Lucknow and attended by many prolific writers from the subcontinent. Ali gave a speech at the meeting in which he expressed the “progressive” change that was needed in Indian society — “it is a painful process in the throes of which India is finding herself today, finding herself between two worlds, the one dead and the other yet unborn.” (Ali “Progressive View”)

During the interim years after Angare’s publication and AIPWA’s inaugural meeting, Ali wrote “Our Lane” (Hamari Gali), written originally in Urdu and translated into English by Ali himself. This story was his early exploration into the stream-of-consciousness technique, which he would sustain throughout his literary career as an early harbinger of literary modernism into the subcontinent. He decided to “take a risk” and submitted this story to New Writing magazine, edited by John Lehmann, poet and founder of various British periodicals. “Our Lane” was published in 1936 in New Writing, as Lehmann “liked it immensely” (Ali and JSAL 152).

Ali also published his first solo collection of Urdu short stories Shole (Flames) soon after. A rift developed between Ali and the other members of AIPWA, particularly Zaheer, due to their contrasting notions on the role of art and artist in society. Ali refused the definition of ‘progressive’ put forth by Zaheer and others, contesting “their point of view that only the proletariat and the peasantry were progressive, that the middle class and the rest of humanity, which did not fall into the group of the worker and the peasant, were not progressive” (Ali and JSAL 148). To him, being ‘progressive’ was “essentially an attitude of mind” (qtd. in Joshi 213). While to the other members, “progressivism as an aesthetic practice became a kind of euphemism for socialist realism”, Ali developed a distinct “form of literary indigenization” that opened a new chapter in modern Indian literary history, by drawing from vernacular Urdu and Persian traditions and regional Delhi/Lucknow influences (Joshi 208-13). Ali distanced himself from the group in 1938 (which affiliated itself with the Communist Party of India) and focused on his next big project.

Ali lived in Delhi over the summer of 1938 when he drafted and sketched out the novel he had in mind by “watching, observing, and imagining” (Ali and JSAL 153). By the summer of 1939, he had Twilight in Delhi typed out and ready to send to publishers. Ali went to England on a study leave where he made E.M. Forster’s acquaintance. The two developed a close friendship that lasted many years after Ali left the country, in the form of letters and occasional visits. Forster introduced him to many who were part of the Bloomsbury group and John Lehmann brought him in connection with the New Writing group.

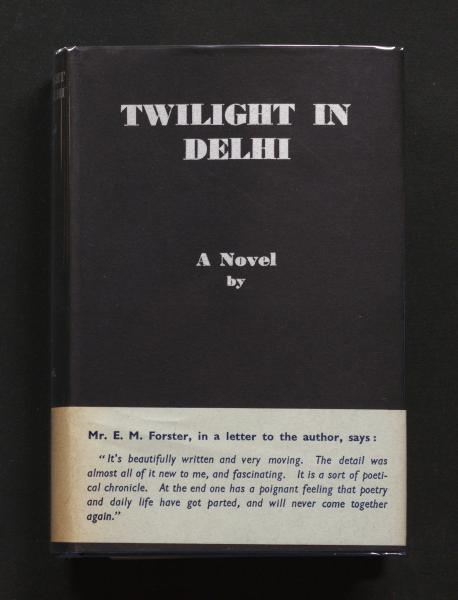

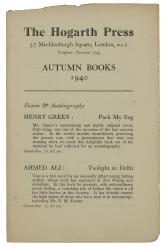

Ali gave his newly finished novel to Forster to read and on his recommendation, reached out to literary agent Spencer Curtis Brown who agreed to take on his novel. Against the backdrop of World War Two, finding a publisher was taking longer than expected, due to evacuations. After trailing after him, John Lehmann proved instrumental in getting the manuscript of Twilight in Delhi accepted to be published under Hogarth Press’s banner, since he was working alongside Virginia Woolf at the time.

However, the road to publication was not easy for Ahmed Ali. Lehmann sent him the galley proofs and a letter which read “I received this letter from the printers in which they say it's unfortunate but they would be unable to print the book.” (Ali and JSAL 159) They had advised that he delete portions of the book that describe the 1847 Indian Mutiny and the 1911 Durbar of George VI, as they were perceived as “anti-British”. Ali had not intended to portray that sentiment as “I wanted to write about what happened to society”. (154) He consulted Forster on the suggested revisions who advised Ali to refuse on the grounds that “you cannot cut out any portion without emasculating the whole”. (159) Forster persisted in getting the novel to the next stages of publication by contacting his friend and literary critic Desmond McCarthy who raised the matter to Virginia Woolf, who approached Harold Nicolson, the official censor. Nicholson passed the book and the printers’ argument was overturned. The book was finally released in 1940, by which time Ali had already left England.

The book opened to favourable reviews from critics in India and England. The Tribune described it as “charming in a simple way” (George 17) and The Spectator called it “poetic and brutal, delightful and callous” (Dobrée 485). E. M. Forster wrote in a letter to Ali that “It is beautifully written and very moving… At the end one has a poignant feeling that poetry and daily life have got parted, and will never come together again.” (quoted in Ali and JSAL 191) This quote was used as a blurb in subsequent paperback editions of the book. Twilight in Delhi “was a singular attempt at vernacularizing the novel with almost exclusively local preoccupations” (Joshi 213) which consecrated Ali’s place in the Indian literary canon of experimental Anglophone writing.

Lehmann published the opening sections of the novel as “Morning in Delhi” in his offshoot Penguin New Writing the following year, which were also reprinted in Atlantic Monthly in 1953.

Ali returned to India and took up a post as the Director of Listener Research for BBC, Delhi. However, he continued his affiliation with England as an editor for Indian Writing magazine (1940-42). He published two more short story collections in Urdu — Hamari Gali (Our Lane; 1942) and Qaid Khana (Prison House; 1944). In 1944, he joined the Bengal Senior Educational Service and was appointed Professor and Chairman at Presidency College, Calcutta. He published Maut se Pahle (Before Death; 1945) during this time.

In 1947, he went to China as a British Council Visiting Professor where he took an interest in Chinese language and poetry, which resulted in Muslim China (1949), an exploration of the Chinese Muslim populations.

During the Partition of India in 1947, Ali was left with little choice, due to miscommunication, and had to permanently leave Delhi for Karachi in 1948. Alongside his work with the Pakistan civil service, he worked with a group of Indonesian diplomat friends to publish arguably the first ever collection of Indonesian poetry in English translation, The Flaming Earth: Poems from Indonesia (1949).

Over the next two decades, Ali published his English translations of Urdu poetry by classic and contemporary poets in The Falcon and the Hunted Bird (1950), The Bulbul and the Rose (1960), Ghalib: Selected Poems (1969), and The Golden Tradition (1973). He also published his own poetry collection Purple Gold Mountain: Poems from China (1960), reflecting on the lasting impression that China had had on him. He published his second novel Ocean of Night in 1964. He founded Pakistan P.E.N. and edited its first anthology of Pakistani writing in English translation.

In 1950, Ali married Bilqees Jahan, a poet and painter who would go on to translate Twilight in Delhi into Urdu as Dilli ki Sham (1963). Oxford University Press reprinted Twilight in 1966 and the American reprint by New Directions came out in 1994, ensuring its resurgence.

During his time in the United States as a Fulbright Visiting Professor in the 1970s, his work on Al-Quran: A Contemporary Translation was first published by Akrash Publishing, Karachi in 1984 and subsequently by Princeton University Press in 1988. In 1985, he published his third novel Of Rats and Diplomats.

Ali was a decorated scholar. In 1981, he was bestowed with the Sitara-e imtiyaz (Star of Distinction) by the Government of Pakistan for exceptional service to the country. In 1993, he received the degree of Doctor of Letters from Karachi University. Three months later, on 14 January 1994, he passed away.

Ali’s works continue to be studied and included in discussions on modern South Asian Anglophone literatures and the history of the postcolonial Urdu short story.

Further Reading

“Ahmed Ali”. Making Britain. The Open University, n.d., https://www.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/makingbritain/content/ahmed-ali.

Anderson, David D. “Ahmed Ali and “Twilight in Delhi””. Mahfil, vol. 7, no. 1/2, 1971, pp. 81-86.

Coppola, Carlo. “The Angare Group: The Enfants Terribles of Urdu literature”. Annual of Urdu Studies, 1 (1981), p. 61

Gopal, Priyamvada. Literary Radicalism in India: Gender, Nation and the Transition to Independence. Routledge, 2005.

Jalil, Rakhshanda. Liking Progress, Loving Change: A Literary History of the Progressive Writers’ Movement in Urdu. Oxford University Press, 2014.

The Two-Sided Canvas: Perspectives on Ahmed Ali. Edited by Mehr Afshan Farooqi, Oxford University Press, 2013.

Morse, Daniel Ryan. Radio Empire: The BBC’s Eastern Service and the Emergence of the Global Anglophone Novel. Columbia University Press, 2020.

Works Cited

Ali, Ahmed and JSAL. “Interview: Ahmed Ali: 3 August 1975 Rochester, Michigan.” Journal of South Asian Literature, vol. 33/34, no. 1/2, Asian Studies Center, 1998, pp. 117–94.

Ali, Ahmed. “Progressive View of Art”, Golden Jubilee Brochure, Ghulam Rabbani Taban Papers, Nehru Memorial Museum & Library (NMML).

Coppola, Carlo. “Ahmed Ali (1910-1994): Bridges and Links East & West”. Journal of South Asian Literature, vol. 33/34, no. 1/2, 1998/1999, pp. 112-116.

Dobrée, Bonamy. Review of Twilight in Delhi. The Spectator, 8 Nov. 1940, pp. 484-85.

George, Daniel. Review of Twilight in Delhi. The Tribune, 29 Nov. 1940, pp. 17.

Joshi, Priya. “The Exile at Home: Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi”. In Another Country: Colonialism, Culture, and the English Novel in India. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002, pp. 205-227.

Bibliography

“When the Funeral Was Crossing the Bridge”. Lucknow University Journal, 1929.

“Mahavaton ki ek Rat”. Humayun, 1931.

“Clouds Don’t Come” and “A Night of Winter Rains”. Angare, 1932.

Shole. Akrash Press, 1934.

“Our Lane”. New Writing, vol. 4, 1936.

Twilight in Delhi. Hogarth Press, 1940.

Extract from Twilight in Delhi. Indian Writing, vol. 1, 1940.

“Morning in Delhi”. Extract from Twilight in Delhi, Penguin New Writing, vol. 8, 1941.

“Morning in Delhi”. Extract from Twilight in Delhi, Atlantic Monthly, vol. 92, no. 4, 1953, pp. 121-26.

Hamari Gali. Akrash Press, 1942.

Qaid Khana. Akrash Press, 1944.

Maut se Pahle. Akrash Press, 1945.

Editor and translator, The Flaming Earth: Poems from Indonesia, 1949.

Muslim China, Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, 1949.

Editor and translator, The Falcon and the Hunted Bird, 1950.

Editor, Pakistan PEN Miscellany, 1950.

Purple Gold Mountain: Poems from China. 1960.

Editor and translator, The Bulbul and the Rose. 1960.

Ocean of Night. Peter Owen, 1964.

Dilli ki Sham, translated by Bilqees Jahan. Maktaba Jamia Ltd., 1968.

Editor and translator, Ghalib: Selected Poems. Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1969.

Editor and translator, The Golden Tradition. Columbia University Press, 1973.

Translator, Al- Qur’an: A Contemporary Translation. 1984. Princeton University Press, 1988.

Of Rats and Diplomats. Sangam Books, 1985.